Feb 2, 2026

Writer: Şeyma Yılmaz Köse

In recent years, the concept of risk for companies is quietly but fundamentally changing. It's no longer just interest rates, commodity prices, or geopolitical developments; soil fertility, water regimes, and the resilience of ecosystems are also becoming part of financial planning. In other words, the loss of nature is turning from an abstract environmental issue into a risk that is measured, priced, and reflected on balance sheets.

This transformation leaves companies facing an unfamiliar question: How does environmental destruction occurring outside their control impact company value? How can an ecosystem disruption in the supply chain change raw material prices, insurance costs, or production continuity?

At this point, biodiversity is gaining a new position on the ESG agenda. Just like Scope 3 emissions, which were once overlooked but are closely monitored by investors today, biodiversity stands out as a risk area shaped beyond companies' direct operations but with direct financial repercussions.

Just as Scope 3 emissions reveal the real complexity of climate action, biodiversity is becoming the next big frontier in ESG. Therefore, an increasing number of experts are defining biodiversity as "the new Scope 3 of ESG."

Why the "Scope 3" Analogy?

This analogy is not a random comparison. Let's recall Scope 3 emissions: the carbon footprint for which the company is responsible but outside its direct control. It is hard to measure and complex to manage with suppliers, logistics, customer use, and similar points; however, when ignored, half of the climate strategy is missing.

Biodiversity works exactly like that.

The impact of a company on nature often manifests beyond the boundaries of its own facilities. Elements such as the land used in the supply chain, water resources, raw material extraction, and indirect ecosystem effects expand this impact area. Control is partly limited, but the financial risk is entirely on the company.

This structure puts companies in a challenging equation: A risk area that you cannot manage directly but cannot escape its consequences.

Why is Biodiversity Loss a Financial Issue?

For many years, biodiversity loss has been treated as an environmental issue. Species that need to be protected, disappearing habitats, sensitive ecosystems, and similar topics were the subjects of nature conservation. However, recent studies clearly demonstrate that the degradation of ecosystems leads to direct financial results for companies.

Is the water cycle weakening? Costs are rising for agriculture and manufacturing companies. Is soil fertility declining? The food supply chain is at risk. Are pollination services decreasing? Global agricultural production is under threat.

Such impacts are no longer just headings in CSR reports; they are becoming agenda items discussed in risk management meetings. Because financial institutions, investors, and rating agencies increasingly regard biodiversity loss as a priceable risk.

Regulations Come into Play: ESRS E4

One of the most concrete indicators of this transformation is the ESRS E4 Biodiversity and Ecosystems standard published under the European Sustainability Reporting Standards. ESRS E4 does not expect companies to make vague and unquantified general commitments like "we protect nature." Instead, it offers a much more specific framework:

How do your activities impact ecosystems?

In what ways are you dependent on these ecosystems?

How is land use, habitat loss, and ecosystem degradation shaping along your value chain?

Therefore, the scope is not limited to the company's own operations. Just like in Scope 3 emissions, the effects that arise along the value chain are also evaluated as a natural part of the reporting and addressed as a whole.

Translating Nature into Risk Language with TNFD

In addition to regulations, one of the most prominent voluntary frameworks recently is the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Similar to the common language created by TCFD on the climate side, a similar structure is being built for biodiversity with TNFD.

The most valuable contribution of TNFD is that it addresses biodiversity from two perspectives: impact and dependency.

Impact: What damage does the company cause to nature?

Dependency: What ecosystem services does the company's business model rely on?

The second dimension is particularly critical. Because a company can carry high risk due to its dependency on nature even if it causes no harm to it. For example, consider a beverage company that is heavily dependent on water resources. Disruption of the water cycle directly threatens the operational continuity of that company.

Or as a reverse effect example, a company supplying palm oil for biodiesel, even if it does not directly cut down forests, indirectly causes habitat loss and carbon emissions due to its suppliers converting tropical forests into agricultural land. This impact may be invisible in the company’s operations, but it directly returns to the company in terms of reputational risk, regulatory pressure, and supply continuity.

TNFD provides a methodological basis for translating such risks into financial language.

Additionally, TNFD suggests that companies conduct geographically-based analyses. Because biodiversity risks are highly dependent on local and regional dynamics, unlike a global carbon footprint. Each geography has its unique ecological sensitivities, and it is precisely for this reason that biodiversity cannot be measured by a single metric.

Let’s think with a concrete example: imagine a company that is heavily reliant on water and operates in a region suffering from water stress or struggling with drought. If this company does not consider water risk in its risk assessment, how seriously can you take that work? Therefore, geographical context is essential in biodiversity assessments.

How do ESRS E4 and TNFD Work Together?

Although these two frameworks were developed for different purposes, in practice they complement each other perfectly:

ESRS E4 answers the question "what will you report?".

TNFD provides methodological solutions to the question "how will you analyze this information?".

When used together, companies can meet regulatory expectations and generate consistent answers to investors' questions on nature-related financial risks.

A Critical Step from ISSB: Nature is Now on the Standard Agenda

At the end of 2025, a milestone occurred in global sustainability reporting. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) decided to develop a new reporting standard for nature-related risks and opportunities. This decision is a strong indication that biodiversity and ecosystem risks are no longer "optional" but are moving to the center of mainstream financial reporting.

This step by ISSB is particularly important because it is said that this board, which is also the architect of the original texts of the TSRS applied in Turkey, is expected to publish a draft standard related to nature by October 2026, before the CBD COP17 summit.

From Voluntary to Mandatory: A New Era in Biodiversity Reporting

ISSB announced that it will utilize the TNFD (Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures) framework during the new standard development process. As a result of this collaboration, TNFD will complete its current technical work in the third quarter of 2026 and focus on the integration into ISSB.

This development is not coincidental. The number of organizations adopting TNFD recommendations has reached 733, representing a total market value of over $9 trillion and assets under management exceeding $22 trillion. These figures clearly indicate how critical nature risks have become for institutional investors.

A Framework to be Built on IFRS S1 and S2

ISSB's approach is to develop nature standards not as an independent reporting line but as complementary to the existing IFRS S1 (General Sustainability Requirements) and IFRS S2 (Climate-related Disclosures) standards. This means that nature risks will be addressed in an integrated manner alongside climate risks.

It is still unclear how ISSB will structure the nature standard. Possible options include a new independent standard, additions to existing standards, or sector guidance. Regardless of the approach, the goal is clear: to provide comparable, consistent, and financially meaningful nature information for investors.

Why Now?

The fundamental driving force behind these developments is investor demand. Scenario analyses, stress tests, and risk assessment tools developed for climate risks are now expected to be applied to nature-related risks such as water scarcity, soil degradation, and ecosystem collapse. Because these risks directly affect a company's long-term value creation capacity.

As ISSB Chairman Emmanuel Faber has emphasized, leveraging the TNFD framework allows for an efficient response to this need, reducing fragmentation and basing practices on leading examples.

The message for companies is clear: Biodiversity is no longer an environmental issue but a strategic business risk. Soon, explaining how these risks are managed will become a standard expectation, just like with climate risks.

Where Should Companies Start?

One of the most common misconceptions about biodiversity is the thought of "first complete measurement and quantitative data, then action." However, research shows that it is healthier for companies to start with qualitative risk definitions and prioritization.

A practical starting point could involve the following steps:

1. Geographic Mapping: In which regions are your activities and supply chain concentrated? What is the ecological sensitivity of these areas?

2. Dependency Analysis: Which ecosystem services does your business model depend on? What is your level of reliance on elements such as water, soil, pollination, and climate regulation?

3. Risk Prioritization: In which geographies and for what activities does biodiversity loss pose the greatest financial risk?

4. Initial Goals and Action Plan: Set concrete goals in priority risk areas. Initially, taking steps in the right direction is more valuable than perfect measurements.

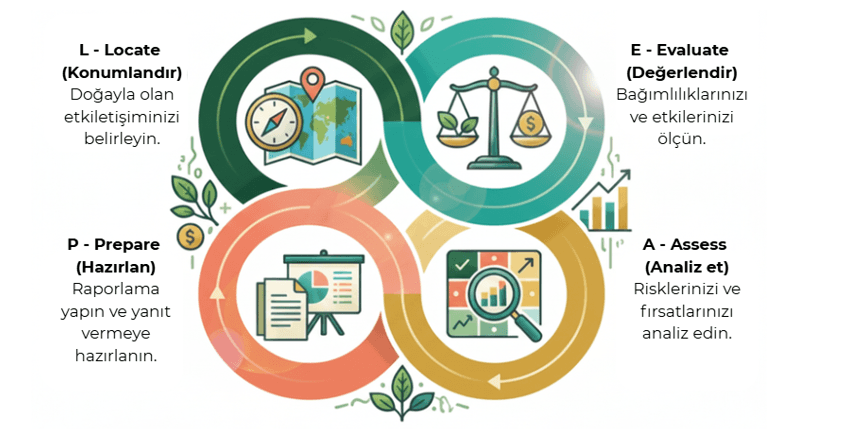

The TNFD's LEAP approach presented in the graph below offers companies a structured method for gradually defining nature risks. This framework systematizes the entire process, from geographic location to risk assessment.

A New Threshold for ESG

Today, biodiversity is at the same point in corporate sustainability as climate was 5-10 years ago: hard to measure, complex to manage, but no longer ignorable.

Just as Scope 3 emissions gradually settled at the center of ESG reporting over time, biodiversity is following a similar trajectory. Regulations are tightening, investor expectations are becoming clearer, and risk perception is changing. For companies that act early and establish the right framework, this process is not just a compliance burden but also represents a strategic advantage. Because biodiversity is no longer just a narrative topic. It is a new threshold for ESG that requires management of risks, dependencies, and financial impacts.

You can contact us for support in biodiversity risk assessment, nature dependency analysis, and TNFD compliance, as well as information about our work in sustainability risks and scenario analyses.

References

IFRS, Objective and scope of standard-setting on nature-related risks and opportunities, Staff paper

Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Aligning Business Strategy with Nature (2025).

TNFD. LEAP Approach Guidance and Nature-related Risk Assessment Framework.

Sustainable Investment Institute (SII). Biodiversity and Business Risk: From Environmental Impact to Financial Materiality.

Liu, Z. (2025). When TCFD Meets TNFD: Can It Revolutionize Corporate Sustainable Risk Management? Business Strategy and the Environment.

EFRAG. ESRS E4 – Biodiversity and Ecosystems: Standard Requirements and Value Chain Implications.

Sustainable Investment Institute (SII). Corporate Biodiversity Reporting: Challenges, Gaps and Good Practices.